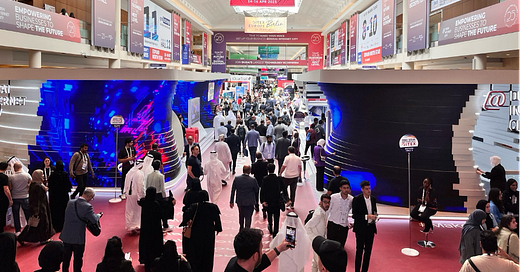

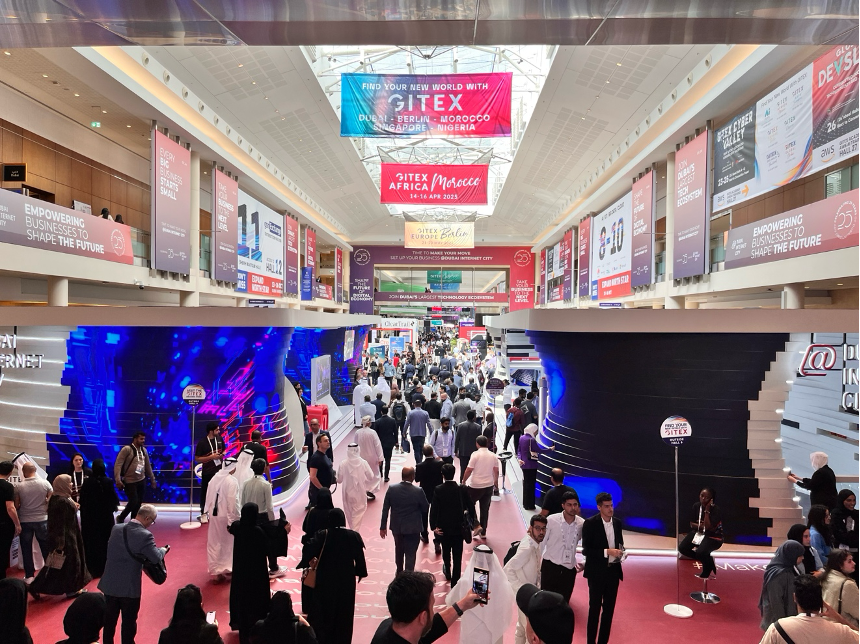

Last week, I spent a morning at the GITEX trade show in Dubai. Organisers call this the largest tech fair in the region, attracting over 6,500 companies—ranging from large corporations and small development shops to chip makers, infrastructure providers, consultants, municipalities, IT heavyweights, and everyone in between.

I remember attending GITEX when I was 15 years old, witnessing the debut of the first black-and-white laser printers. Back then, it was held under a big tent next to the World Trade Centre, and the entrance fee was Dhs 25 (about 8 USD).

I had no real agenda for the day apart from just going with the flow and seeing what’s on. I naturally gravitate towards anything relating to fintech, but I knew this was not that type of event. The floor plan was laid out to cover a few ‘big themes,’ such as AI, Gaming, GSM, Cloud, IoT, Digital Cities, and so on.

As I strolled through the booths, I came to the realisation that the whole trade show felt like an AI showcase of sorts and that technological innovation, at least according to GITEX, has now become synonymous with AI innovation. It was hard to find an established exhibitor that didn’t showcase their ‘AI offerings’ front and centre; hardware, chatbots, assistants, language models in different languages, and all sorts of derivative applications were on display.

How does is AI applicable to the investment industry? I did have some prior views on and ideas of how AI would affect capital markets (both on the buy and sell sides), and seeing some of this on display validated some of my assumptions to some extent.

Large institutional investors have been crunching massive amounts of data for decades, consistently investing in technology, including machine learning, to improve data quality, processing speed, and trading operations. Michael Lewis’ book Flash Boys gave us a glimpse into this world a decade ago, showing how high-frequency traders used cutting-edge tech to gain microsecond advantages in the market. Automating the analysis of financial reports, news, extracting insights, sentiment, identifying patterns and anomalies, detecting shifts in public sentiment (after all, you make money not by being right about the company, but by being right about what others think about the company!) has been around for a long time. But they were expensive, inefficient, and accessible only to the largest institutions.

The difference with generative AI (a much more intelligent technology that comes up with data and smart workflows based on training) is that it levels the playing field somewhat, allowing smaller, less-resourced startups or boutique fund managers (or even sophisticated retail investors) to compete more effectively with larger firms by giving them more compute power. Just as an amateur software developer can now write, check, and debug more code than ever before—delivering higher-quality software faster and at a lower cost—AI tools enable active fund managers to vastly expand their analytical capabilities. By processing vast amounts of data points, research, identifying patterns, and automating routine tasks, fund managers are freed up to focus on what truly matters: developing high-conviction investment ideas backed by good data.

So, in a world where AI tools enables thousands of investors to process, crunch and analyse the same vast amounts of information, the value of personal connections and unique insights will only grow. Therefore, direct engagement with companies—insights from conversations that algorithms can't replicate—will become even more essential for gaining ‘an edge.’ In other words, with data and data analysis increasingly commoditised and accessible, the human element of understanding a company will be more sought after than ever.

Beyond AI, a few other things caught my eye at GITEX. I bumped into a South Korean delegation and spoke to a few companies there: one developing an optical glass headset with an on-off digital canvas switch; another creating a 3D virtual world where you walk with your digital self through an easily customisable environment. A third company, Deepbrain, was developing virtual avatars that looked remarkably realistic. I could easily replicate a digital version of myself, teach it what to say and how, and use it to present the weather forecast with an English accent on BBC News…

My high-level, and somewhat raw, view here is that we’ll see a continued convergence of the virtual and real worlds, first through augmented reality (AR) or a physical world overlay experienced through hardware that people will want to use. Practically, you could be visiting the Louvre, and instead of putting on a clunky headset, you'd have an on/off toggle on glasses, contact lenses, or whatever, to see a small virtual tour guide, who looks and feels like a real person, walk you through the exhibits. Your digital real estate would shift from being on a phone screen to being directly in your eyes—and it’s easy to see why companies like Meta and Apple are investing billions in research in this space. This shift would change how brands engage with customers, creating new digital real estate on top of the real one. And of course, it’s easy to extrapolate and visualise applications in other industries, for example, education. Imagine a history lesson watching an actual re-enactment of a gladiator fight in Rome’s Colosseum with a digital twin of Julius Caesar as your host.

Augmented reality, by nature a ‘mobile’ experience, will coexist with a ‘sedentary’ virtual (so called VR) world which has become increasingly synonymous with ‘metaverse’ . Many people get turned off when they hear the word metaverse, but I just think of it as a 3D version of the browser. From that perspective, we’re already there. If you’ve played the recent MS Flight Simulator, cycled indoors with BKOOL, or played golf in a Trackman environment, you’ll know how good the immersive 3D virtual worlds have become. In fact, they’re so good that sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference between the real and the virtual.

The challenges to make this happen at scale are largely technical, but many analysts look at this space with the view that it will get there within a 10-year horizon. The opportunity then will be for companies to find creative and intelligent ways to be present and interact with their customers and investors in the ‘simulator experience internet.’ Until then, new paradigm in web seems to be ‘AI + mobile’.

Before I left, I stopped by the smart city pavilion, which was dominated by governments showcasing innovation in digital identity, healthcare, and city management. The big questions being addressed by the smart city folk are worthy ones in which we all in a way have skin in the game: how can our cities and urban areas become more attractive and liveable? How do you build (or improve) a city to maximise the well-being of its citizens? Many cities that have the luxury to start from scratch (e.g. NEOM) experiment heavily (e.g. GITEX host city Dubai), others do it more modestly but consistently (e.g. London), and some almost none at all (e.g. Milan, the city where I studied 20 years ago looks almost identical now to how it was then).

Even though GITEX often gets bad press locally for being a ‘hype fest,’ with people complaining it’s too crowded, I think the atmosphere was one of optimism, that the future is envisaged to look better than the present. And if nothing else, having a festival to celebrate this sort of mindset is a good enough excuse to throw a tech trade show!