A few months ago, I listened to Charles Lyle from GS discuss some reasons why the London Stock Exchange has been losing its mojo why some UK companies are considering switching their listings abroad.

The debate in the City of London1 continues on this, with various working groups being created, including the Capital Market Industry Taskforce, whose goal is to ‘maximise the impact of capital market reforms’. Similar projects aim to provide policy recommendations and propose long-term changes to overhaul the rules for companies looking to list their shares in London instead of elsewhere (read: New York). And things seem to be moving. Last month, the UK financial market regulator, The FCA, approved what seems to be one of the biggest changes to its listing rules in decades2. It is in a bit of a tight spot : on one side The FCA is under pressure to be more commercial, but equally wants to preserve high corporate governance standards. Drawing the line in the right spot is tricky. The initial reaction to the recent changes has been positive, though as we all know, these changes take years to fully implement and perhaps longer than that to see the effects come through. Surely there will be more to come on this.

When companies discuss listing venues with their advisors, they usually consider what they get: access to capital (i.e. valuation) and liquidity versus what they have to give in return: costs and ongoing requirements (disclosure, corporate governance compliance, additional litigation risks in the US3, etc.). In many cases, decisions often go beyond pure economics, sometimes involving political decisions from up above. e.g., governments wanting their country's "crown jewels” (e.g. Saudi Aramco comes to mind) to be listed at home rather than in some far-away market. Similarly, trade wars or trade policy disputes, such as those between the U.S. and China, can have an impact.

However, the access to capital element is somewhat tricky to completely isolate and quantify. For most large active institutional investors, it doesn't really matter where a company is listed or traded—large funds can buy US equities as easily as they can buy South African ones. Yes, vis-a-vis frontier markets, investors do place a premium on companies adhering to the relatively higher standards of the LSE or Nasdaq, which acts as a sort of seal of approval. For smaller funds that need to hold assets in USD or lack the capability to trade globally, depositary receipts4 (DRs) have historically filled the gaps for both developed and emerging markets. However, DRs for most part, do not give companies access to the entire investment universe in a given market, and the reason for this is that they trade on carved-out section of the exchange (e.g., the International Order Book in London, or the 144A market for ‘qualified institutional buyers). These sections, while allowing on large active institutional investors, do not permit retail and passive investors to participate. But this is precisely where the growth has been taking place over the last decade.

Both retail investors and passive investors have been on the rise over the last decade, and both groups struggle to access the full gambit of international equities the way large portfolio managers can.

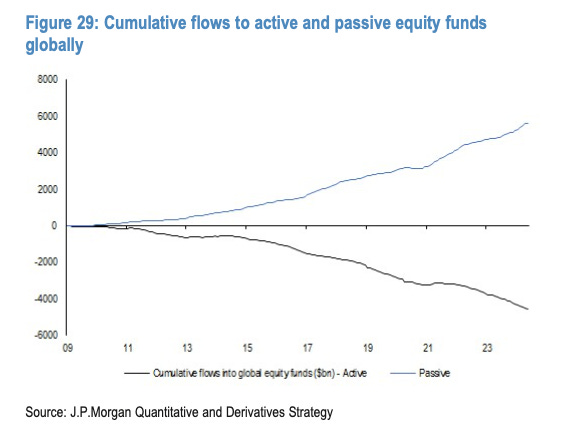

Last week, JP Morgan published a piece that caught my eye. They argued that one of the advantages of listing in the US is indeed access to greater passive investment. According to their estimates, various index funds hold 20-50% of US-listed companies. In Europe, passive ownership ranges from 10-25%. Unlike an active investor, which has more flexibility to access the instrument abroad, passive funds (such as ETFs) have much less of it, and are more tethered to an exchange.

Furthermore, as we have seen and heard for a while, active fund managers on the whole, have delivered (at best!) mixed performances versus their benchmarks in recent years, which is exacerbating the flow of capital into passive funds. Just look at the data:

JP Morgan also looked at a few companies that have moved their primary listings from Europe to the US in the last two years: CRH, Ferguson, Flutter, Linde, and CNH5. They concluded that the valuation gap between these companies and their US peers has indeed narrowed since the listing move, and both passive and active ownership of these stocks has increased since a year before the listing change.

As a result, the US capital market has been gaining popularity in Europe: the number of EU companies seeking single and dual listings in both the EU and US, as well as European companies with ADRs, has increased. And interestingly, the main contributor could have been passive institutions6, assets of which have been increasingly concentrated in just three institutions which we will talk about in the coming posts.

As we have written about earlier, for the London Stock Exchange Group, the ‘exchange’ part is negligible. The debate is not about boosting revenues for the parent, but rather bringing back the old glory of London being a global listing epicentre of capital markets. But no only in London; financial centres around the world look at their exchanges not as data providers but still as traditional listing and trading venues.

The changes include amongst others, permitting dual-class share structures, removing the requirement for shareholder approval for certain transactions, and lowering revenue requirements for listing. Many of those are supportive for technology

In 2022 alone, 208 securities class action suits were filed in the US, including 34 against non-US issuers.

There are over 2,400 depositary receipt (often referred to DRs, ADRs, GDRs) globally. Those receipts (like a ticket in a cloakroom) represent the underlying ordinary share and pass ‘through all’ corporate actions like dividends. They are fungible (ie DR in New York can be exchanged into a Kazakh ordinary share). There are also various types of receipts, ranging from OTC (‘level 1 DR’), to a fully fledged listing (‘level 3 DR’).

Each of these companies has compelling operational reasons to migrate their listings to the US. CRH earns 75 per cent of its ebitda from North America; Flutter’s biggest revenue stream comes from US-based sports bookie FanDuel; and Ferguson’s operations are now “100 per cent North America”.

It is also probably worthwhile to pause and state the obvious: a listing on the US exchange (or any other exchange) does not automatically guarantee passive investment. The point that I think JP Morgan is trying to make (along with its case studies) is that, in a like-for-like comparison between companies listed in Europe versus the US, the latter will attract more passive fund flows.