The Loyalty Dividend

Exploring opportunities and risks of the intersection between customer loyalty and retail investor engagement

Some time ago, I wrote a post and coined the term ‘Investomers’ - the so-called individuals who are both enthusiastic brand lovers and customers of company products and investors in your stock (or vice versa).

I even allowed myself to jump the gun and suggested that blockchain-enabled ‘company’ tokens could one day provide a toolkit for an upgraded 2.0 version of loyalty programs, with a tradable asset that could have all sorts of other uses for both private and publicly listed companies alike.

I also noted that there aren’t many companies today focusing on unifying those two worlds; attracting and retaining customers and retail investors. However, it turns out that there are some. Let’s check out a few of them:

Orlen, one of the largest oil refineries and petrol retailers in Poland and Eastern Europe, launched ‘Orlen in the Wallet’ programme for retail investors in 2018. You join the club by investing in at least 50 Orlen shares (at today’s prices, roughly $1,000), and in return, you get a discount on petrol at their stations as well as a 10% discount on other products. Since 2018, Orlen has welcomed over 10,000 new retail investors.

Air Liquide, French leader of industrial gases (and hardly a consumer stock!), rewards long-term retail investors by awarding them with extra shares1 : 10% extra dividends and 10% ‘free shares’ if you hold the shares for over two years. This has resulted in over half a million individual investors holding 33% of shares and voting rights, most of whom give their proxy to the president, providing useful support in contentious corporate governance situations2.

LVMH, one of the world leading fashion groups, boasts a ‘Shareholder Club’ tailored to individual shareholders who show a special interest in the Group. The LVMH Shareholders’ Club offers its members special offers on products, access to a dedicated website, and site visits.

Carnival Cruises, an international cruise line based in Miami, rewards shareholders holding a minimum of 100 shares with $250 in onboard credit per year. Other cruise operators such as Royal Caribbean and Norwegian have followed suit with similar programs to compete for customer loyalty.

Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett’s investment conglomerate, owns GEICO Insurance. As a unique perk, Berkshire Hathaway shareholders who own even a single share of stock are eligible for an 8% discount on their auto insurance premium.

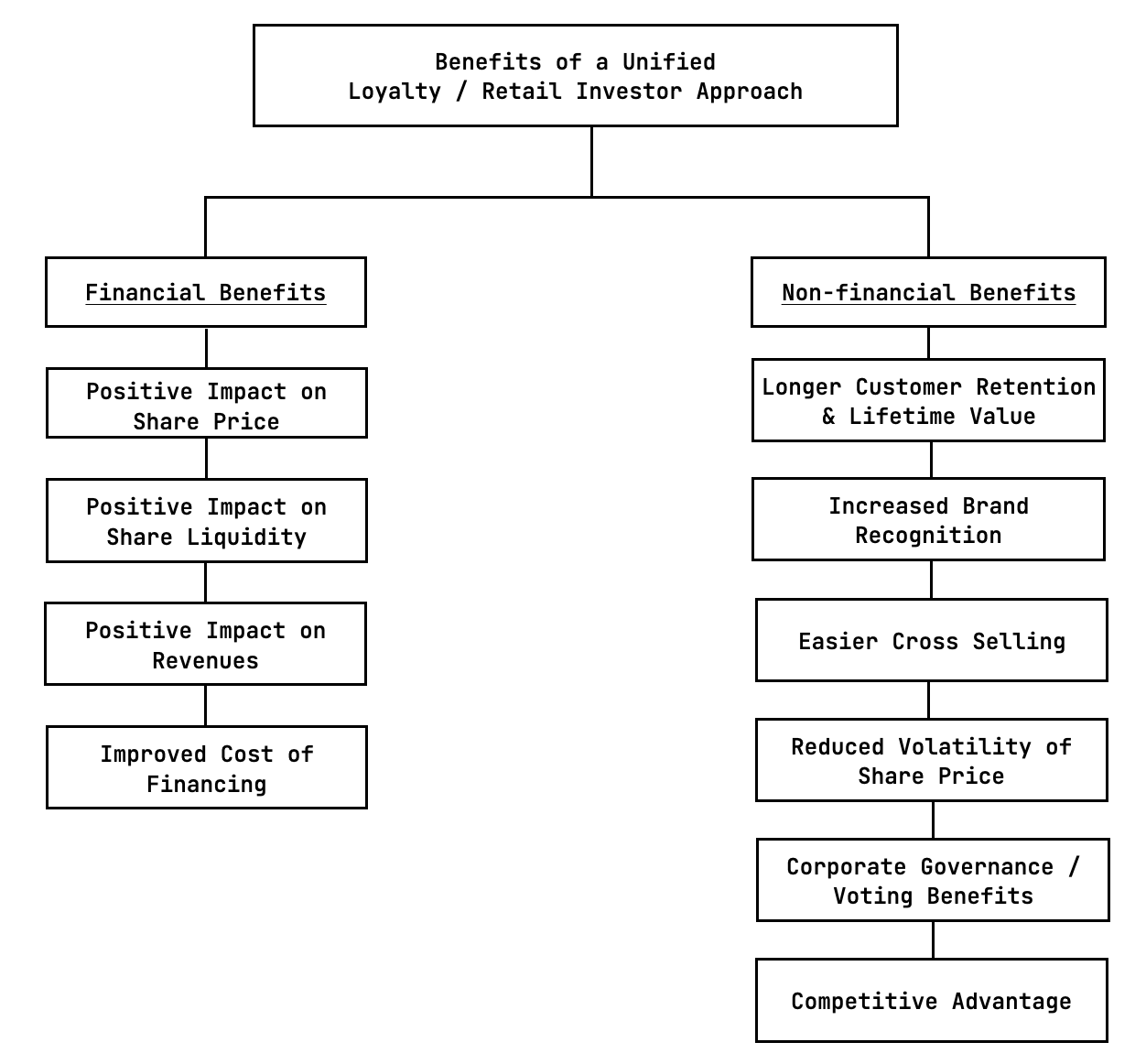

From the outset, the benefits seem obvious. Retail investors and customers like to feel special3 (who doesn’t ?), and nurturing the relationship with this community ensures they stay, buy more shares, purchase more products from your stores, and talk about it to all of their friends.

And the resulting side effect of this approach is the creation of a direct relationship between the company and its key audiences, which has been, over the years, eroded by all sorts of middlemen, delivery apps, e-commerce aggregators, resellers, agents etc.

However, there are also clear challenges that prevent the easy adoption of such unified programs, and ample examples where the programs were discontinued. What are the key challenges and considerations?

Structural: The culture of retail investing needs to be talked about. Countries exhibit varying levels of retail investing culture, influenced by factors such as financial literacy, regulatory environments, and economic conditions. For example, it is a well-known fact that the U.S. has a well-established retail investing culture, with about 60% of households engaging in stock ownership4. The rise of online trading platforms and investment apps has further fuelled retail participation, making it easier for individuals to invest. In Europe, Sweden stands out, with about 22% of households directly owning stocks, supported by a favourable tax environment for investments and a robust capital markets ecosystem that encourages retail participation. In contrast, the Middle East region sees varying levels of retail investment. However, the ‘sophistication’ or interest of those retail investors also vary. Many seasoned IR teams tend to think that ‘an hour spent with retail investors is an hour too many,’ and in many markets, retail investors either focus only on dividend stocks or speculate on stocks that will ‘double in value’, with little interest in engaging with the company or being bogged down by details of the investment case.

Administrative: One of the key operational challenges is being able to identify shareholders in real time to match them with a loyalty benefit. A significant issue within the majority of public markets is the inability to identify shareholders accurately. This is related to the structure of stock ownership, regulatory environments, and the mechanisms of the stock market, with many middlemen (broker, custodian, clearing house) standing between the company and the end investor. In their research paper Berger, Solomon and Benjamin studied 12 shareholder rewards adopters in the US and concluded that more than half dropped their programs due to ‘difficulties in determining whether there has been a change of beneficial ownership.’ Several solutions partly address this issue (e.g., SRD II regulation in the EU, data feeds from custodians in places like Brazil and Saudi Arabia), but none are perfect.

Legal: When designing a program that unifies customer loyalty with retail investor, companies must also navigate several legal topics. Capital market regulations, such as those mandating equal access to material information, ensure that no investor receives unfair treatment or privacy laws, like the GDPR, that protect the identities of private investors, requiring companies to handle personal data with care and transparency. Additionally, consumer protection laws mandate that any perks offered to investor-customers are clearly communicated and delivered without deception.

Financial: Firstly, the time and effort required to design a program like this involve several people and resources. For many existing programs, it took two to three years of planning. Secondly, there are costs associated with communicating, launching, and maintaining such a program. Thirdly, getting the reward balance right is crucial. Offering perks and benefits comes at a cost5 but the benefits might not be meaningful enough (or on the flip side, too costly) to make a difference. Striking the right balance could be challenging.

Then there are all sorts of reputational risks that need to be anticipated and managed from the get-go. If the program fails, how will retail investors, equipped with social media handles, react? Some negative experiences can quickly snowball into widespread criticism. A poorly executed program might not only alienate loyal customers but also damage the company's brand and do the opposite of what it was meant to.

Having said this, my personal view is that this will be an area of development and growth. There are a few high level trends blowing wind into the sails here.

Firstly, the activity and sophistication of retail investors are increasing. Individuals are becoming more savvier about their savings and what they own. Secondly, while the concept is not new, there seems to be more focus on the ‘experience economy,’ with businesses focusing on creating unique, engaging, and personalised experiences that resonate emotionally with customers. Thirdly, AI-generated mass-production engine will give way to a renaissance of sorts—a nimble, community-led company that provides a deeply personal products, services and experiences (both on and offline) for its audiences. And lastly, technological advancements will make it easier for companies to make all of this happen. The archaic capital market structure we see today will eventually evolve. Whether blockchain technology or something else will provide the leap forward remains to be seen.

Bringing it all together

While integrating customer loyalty with retail investor benefits is intriguing and presents clear opportunities for fostering deeper brand connections and increasing shareholder engagement, it also faces significant operational challenges and risks that varies from market to market, and industry to industry. Due to these challenges, the concepts discussed here remain fairly nascent and is currently only seen on the fringes of the capital market, with only a handful of companies providing useful case studies.

There are reasons to watch this area with optimism, as many of the challenges and risks are being addressed and will be resolved in the future!

This is referred to as a ‘tenured voting’ system and is the practice of awarding additional votes to shareholders based on the duration of their ownership of the stock. This system contrasts with the traditional "one share, one vote" principle, and it essentially seeks to address concerns about ‘short-termism’ in corporate governance. These systems are now commonplace in France, Italy, and Belgium.

According to recent case studies in France, incentivised retail investors tend to vote in favour of management.

Regulators reading this will cringe. Selective disclosure laws generally prohibit public companies from treating investors differently or providing extra information to specific investors and are designed to promote fairness and transparency in the financial markets.

Having said that, US stock ownership remains very skewed towards wealthy households. As of 2023, the top 10% of American households held 93% of all stocks, the highest level ever recorded. In contrast, the bottom 50% of Americans owned just 1% of all stocks and mutual fund shares.

In financial accounting, loyalty programs are typically accounted for under the "deferred revenue" or "liability" approach. When a customer earns points or rewards through a loyalty program, the company records a liability on its balance sheet, reflecting the obligation to deliver goods, services, or discounts in the future. Revenue is then recognised when the points are redeemed by the customer or when the likelihood of redemption becomes remote, which reduces the liability.