In a recent article, Brian Armstrong at Coinbase shared a few intriguing thoughts. One idea that caught my eye was about the capital market.

He wrote:

The ICO craze had some major challenges – including scams and unregistered securities. But there was a frenzy there for a reason: capital formation globally is still way too high friction. It's also unevenly distributed. If you're an entrepreneur living in Budapest or Bangalore, your chances of having access to capital are lower than if you live in Silicon Valley or Cleveland. We'd have way more startups if it were easier to raise money. (Not just startups: real people raising money for an apartment complex, or anything.)

What would the next iteration of ICOs look like that was legitimate and trusted? Imagine some combination of Stripe Atlas and AngelList in Web 3, that not only helped you register your company or idea (in each country, by filing paperwork, or as a DAO, pseudonymously), but then also helped you raise money for your idea. Each idea could have a pitch deck or video, discussion and ratings, the reputation of participants, and a transparent flow of funds on chain. Democratizing fundraising could unlock tremendous latent entrepreneurial energy across the world.

I wanted to spend some time unpacking this while also exploring what an on-chain capital market could look like. For this post, I'll focus mainly on the equity markets, setting aside the 'Stripe Atlas' part for another day.

A lot of my thoughts below were developed over a few cold ones with Erik Renander, who also publishes an excellent newsletter (

) during a lovely, warm late-summer evening in London.Setting the Scene

Capital formation is, in essence, the process by which businesses—and governments—raise long-term funds. There are two aspects to it: first, the capital market helps companies raise this money from investors. Second, it allows existing owners to trade these securities, adding liquidity and helping to figure out what these assets are actually worth.

In public markets, the primary function of raising capital is usually handled by brokers and investment banks. The secondary function, which involves trading, is overseen by exchanges and comes with a thick layer of intermediaries like registrars and custodians.

In private markets, such as those in private equity or venture capital, the primary function is often carried out by the company seeking funding itself or by a specialised advisor relying on a close network of investors. Trading in the secondary market is usually far less liquid, and many of these assets trade over-the-counter, if at all.

Then there are other asset classes—commodities, currencies, real estate, art or even wine. Each has its own quirks: varying risk profiles, liquidity, expected returns, each operating on its own defragmented capital market stack.

For a global investor this poses number of challenges.

Firstly, navigating multiple markets requires juggling different advisors, each adding to the overall cost. Also, each market has its own set of rules, trading hours, local regulations, corporate governance codes, accounting principles, all off which makes the whole ordeal quite a challenge.

Secondly, for anyone who isn't a major institutional investor, assets tend to be largely 'idle,' meaning they're not actively working for you. Unlike big players who can easily leverage their holdings, the average investor finds it challenging to use these assets as collateral for loans or other financial maneuvers. Essentially, your assets are stashed away in a custodial vault, collecting dust until you decide to sell. This lack of financial agility can be a drawback, especially for those looking to maximize the utility and earning potential of their investments.

Thirdly, the limitations of working with a specific set of counterparties make it easy to miss opportunities in the primary market. For instance, if you're a small European fund manager focused on healthcare, you may never hear about an IPO for a hospital chain in Brazil. Yet, both you and the investor might be eager to engage. The current infrastructure doesn't really support global transactions like this. This issue is magnified if you're a family office or a savvy retail investor. This notion resonates with Brian Armstrong's point about an entrepreneur in India having less access to capital than someone based in the U.S. On the flip side, if I'm a company looking to raise capital, I'm dependent on brokers and investment banks that have 'access' to investors.

Even in the most liquid segments of public markets, companies often gripe about a) the cost of underwriting, which can be between 3-7% of the total deal, and b) questions about whether the cost of equity could be reduced and if more investors could be included. After raising capital, many large listed companies ponder how to diversify their shareholder base. How can they attract the incremental investors from Asia or the Middle East?

The problems magnify as we move down the market cap scale. Large global investment banks are less inclined to work with smaller companies raising smaller amounts of capital. Regional brokers or advisors, on the other hand, lack the global reach and are often confined to a local investor base. This means that a small real estate company in Egypt wouldn't have an obvious route to raise, say, $30 million from global investors, regardless of how compelling the opportunity might be.

Sure, one could argue that the existing system ‘works’ well enough; companies go public, startups get their funding, and perhaps the projects that fail to secure financing weren't up to snuff. One could also argue if there is a group to create new financial products to address the problems above it is the well capitalized banks and talented financiers themselves.

However the incremental improvement mindset is misleading. When you examine the process from inside out, it is easy to spot significant systemic level improvements that take, at the current level of progress, centuries to improve.

So to summarise:

Problem 1: The current infrastructure is outdated and ill-suited for a truly global capital market addressing the needs of widest possible variety of investors. Issues include access, interoperability, inconsistent 'rails,' and barriers to entry.

Problem 2: Matching investors with investment opportunities (and vice versa), whether in primary or secondary markets, typically involves third parties. This results in a) high costs, b) exclusivity, and c) suboptimal efficiency.

So, would a blockchain-enhanced capital market solve these problems for both investors and companies? Maybe.

Let's dive deeper.

Pieces of the Capital Market Puzzle

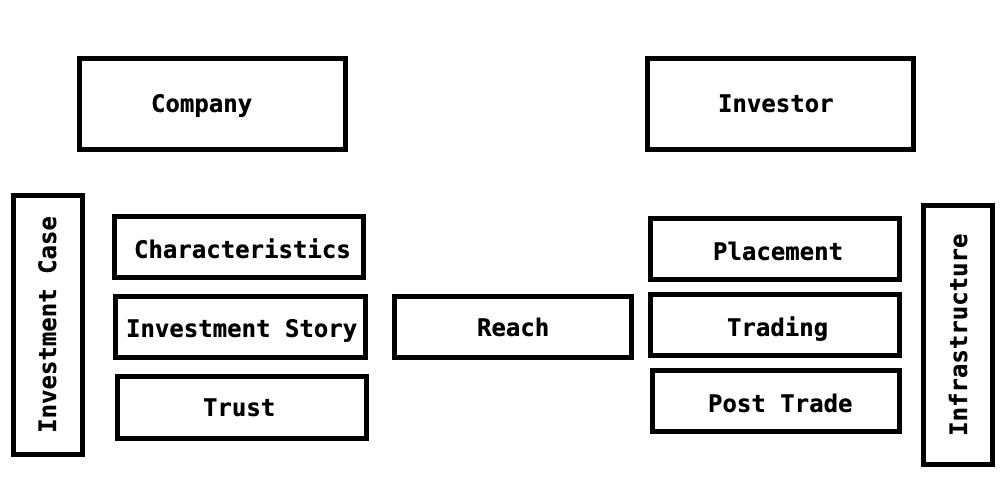

There are five key areas that make up the capital formation picture:

Let’s take a look at each of those in turn.

Characteristics of the Company: This answers the question: What am I looking at? For startups, the characteristics (or attributes) might look something like "UK incorporated, first fundraising round, 3 people, MVP in the market, 3 clients, $5,000 MRR, Regtech, Raising $3m." For a listed equity, it might be "UK based, consumer discretionary, $30m market cap, $500k daily trading value, $1m EBITDA, trading on the LSE."

These characteristics speak to the mandate of an institution or individual, i.e., the universe where it can invest. For instance, an emerging market fund might only be able to invest in companies that are liquid (e.g., trade over $1m) and are based in one of the defined 25 or so emerging countries. Similarly a ‘Latin American healthcare’ venture capital fund might be able to only look at one specific geography and industry. So, the characteristics define what the company is and what the addressable investment universe might look like.

In some areas of the capital market, the model for presenting these fundamental characteristics is well-defined (e.g., in debt markets, some characteristics are even stated in the name). In others, it's more wishy-washy. Also accessing this information is not straightforward because a) the characteristics template is not standardised and b) the ones that are, often reside behind pricey financial terminals, each with its own template.

On the other side, knowing precisely what the mandate of the investor is can be tricky, especially when dealing with private markets or in cases where mandate is loose (e.g. “global investor looking at anything interesting”).

Investment Story: This goes beyond the characteristics and tackles the question, "Why is this company interesting?" or "Why should I invest in this?" and is arguably the toughest element to objectively standardise. Companies often address this by creating polished presentations that dive into the business model, financials, strategy, traction, and so on. Broadly speaking, these presentations serve two purposes: 1) to educate, and 2) to excite the investor about the company's growth potential and future. Various supporting materials are also available, like annual reports in public equities markets or a prospectus for companies about to go public. Seasoned fundraisers often say that convincing an investor is both an art and a science, and let's not forget the personal biases that can come into play.

In the existing landscape, brokers excel at understanding both the mandate and the interests of investors. However, people change jobs and interests evolve. It's challenging to keep everything up to date. Plus, there's a limit to how much you can store in your head or in address book or to keep organised who said what?Trust: This answers the question, “Is this definately not a scam?" In the context of investment, a key component is how much we 'trust' the company. Trust can be a multifaceted topic. For an investor, it might revolve around the credibility of the founder, their past projects, existing investors, or even the company's location. This is why large 'bulge bracket' investment banks that underwrite or 'cover' stocks tend to excel at raising capital. They put their name behind the deal. It also explains why funding at the lower end of the spectrum also often hinges on personal relationships.

Reach: This answers the question, "Who could be interested in this?" It's a function of the investors who can invest (based on the mandate), those who are willing (based on the investment story and trust), and ultimately, the ability to know who they are and reach them. This brings up an issue of information asymmetry and the subsequent challenge of matching supply and demand on a truly global scale.

From the company's perspective, the questions become: How do I know who's interested in my company? And once I identify them, how do I reach out? While operational aspects like book-building have seen some automation, large portions of the fundraising process remain manual, often involving a team of banks, lawyers, and personal connections.

And a large part of the process is manual, exactly as it was twenty years ago. I've seen call notes from a large investment bank to its top institutional investors on excel that include remarks like "not interested right now," "couldn't get through," "away, asked to call back later," etc.

There's a an opportunity here for a ledger-based, global-from-day-one capital market that operates with live supply/demand matching.The Infrastructure: The current systems for buying, holding, and trading shares are far from optimal. For someone who is not savvy on the internal workings of the capital market few things might immediately stand out.

Take, for instance, the trading hours for US equities: a mere slice of the day from 9:30am to 4pm, five days a week. Excluding holidays, this leaves the market open less than 20% of the time. Why can't it be as accessible and trade around the clock?Moreover, the settlement process for equity trades is also outdated. Despite improvements over time, it still takes days for trades to fully settle due to legacy systems.

Finally, accessibility. For many people, especially in developing countries, acquiring equities is far from straightforward. Even in developed markets, you will struggle to easily buy Australian, South African, Canadian and Polish shares in one place.

What if we could tokenise traditional assets like stocks, bonds, commodities, and even currencies, making them accessible to anyone with a smartphone, tradeable 24/7, and settling almost instantly in your digital wallet? Like stablecoins, these assets would still be issued centrally, but they'd represent a far more efficient digital bearer asset. This leads me to my next point.

Envisioning an On-Chain Capital Market Run on Code

If we get creative, we can try to imagine how a capital market might look like in the future.

Each company's essential attributes and investment story would be encapsulated in a smart contract, linked to a fundraising agreement, detailing out when and how the company is planning to raise funding. This would pave the way for a global database of these smart contracts, accessible to the investment market via an API. This digital ecosystem could revolutionise how global investors access this deal flow and automate transactions.

For instance, investors could sift through 'smart contract' offerings or even program algorithms to automatically invest when specific opportunities arise—such as purchasing shares in a particular company when a set condition is met. This level of ‘programmability’ could significantly streamline the capital-raising process, cutting out the cumbersome network of intermediaries, and vastly broaden the reach for both parties. Investors could directly target deals that align with their interests by programming filters for company types, deal sizes, regions, and risk profiles. This focused approach would substantially declutter the influx of potential deals landing in their inbox.

To address the infrastructure question, we could imagine investment opportunities would be 'tokenised,' meaning its underlying infrastructure would be asset-agnostic. Whether you're trading an NFT, shares in an Austrian company, a real estate fund, or startup equity, the clearing and settlement processes would be seamless.

A reliable reputation protocol could offer risk assessments by considering a multitude of factors—ranging from the credibility of the founders to the profiles of other participating investors.

And once you possess a token, like in DeFi, the doors open to a myriad of other transactions. Hold it, stake it to secure a network, lend it, or provide liquidity to a decentralised exchange. The beauty here is the absence of a traditional banking institution acting as an intermediary, thereby maximising your earning potential and minimising risk.

Parting Thoughts

The limitations set by an outdated capital market—constrained by geographical boundaries, lacking in global supply/demand matching and trust protocols, and entangled with intermediaries—have kept the global capital market from being truly 'global' and 'open.'

While blockchain based tools for value transfer, coupled with an asset-agnostic 'rail stack,' may not have all the solutions to these challenges today, they do offer compelling hints into how this could be achieved in the near future.

Mike..... this is such a good post... absolutely massive. You summarised everything really well.